|

|

Bunya Pine

Previous

Next

Up

Home

If you've ever been a passenger in my car then you've probably been asked to get out the refedex and mark the location of some bunya pines. These are truly majestic trees. They look like something out of Jurassic Park. Close up, they have very spiky leaves and you will need shoes on if you walk on them. They can be easily spotted from a distance because they tend to be tall and have a characteristic dome shaped profile and unusually deep green foliage. Even if you can't make out the profile due to a green background, you can often pick them out by the colour. The branches grow sideways and get longer over the years, then eventually fall off when they get too long, usually because they get hit by a falling cone. This is why the trees develop the characteristic domed crown, with shorter 'new' branches growing below, again getting longer with age, but not reaching the size of the crown branches.

Every year during January and February they drop large green cones. Inside each cone is 50 or so nuts, each larger than a big thumb. These nuts are best roasted on a fire and will pop after a few minutes. They can also be cooked on a BBQ grill. I have seen pieces of shell hit the roof of a veranda above a BBQ as the nuts pop, so I cover them with an old pan. I usually have some frozen so I can boil them later in the year. This requires a bit more effort as you have to peel each one. Needle nosed pliers work best for this. I then put them in the fridge and use them in just about all of my cooking. I also make a spread for toast by blending them with honey. They are a cheap alternative to pine nuts - see the basil article for a pesto recipe. I have heard them compared to roasted chestnuts, however having never tasted roasted chestnut I cannot verify this. They can be eaten raw when fresh. If you can figure out a way to peel them automatically without damaging them you could make a lot of money, as this is what is currently holding back commercial production.

Every year during January and February they drop large green cones. Inside each cone is 50 or so nuts, each larger than a big thumb. These nuts are best roasted on a fire and will pop after a few minutes. They can also be cooked on a BBQ grill. I have seen pieces of shell hit the roof of a veranda above a BBQ as the nuts pop, so I cover them with an old pan. I usually have some frozen so I can boil them later in the year. This requires a bit more effort as you have to peel each one. Needle nosed pliers work best for this. I then put them in the fridge and use them in just about all of my cooking. I also make a spread for toast by blending them with honey. They are a cheap alternative to pine nuts - see the basil article for a pesto recipe. I have heard them compared to roasted chestnuts, however having never tasted roasted chestnut I cannot verify this. They can be eaten raw when fresh. If you can figure out a way to peel them automatically without damaging them you could make a lot of money, as this is what is currently holding back commercial production.

The Aborigines used to have large gatherings once every three years when there was a bumper crop. This is no doubt a strategy the trees developed to get around the swarms of sulphur crested cockatoos that rip the cones apart while they are still on the tree to get at the nuts. The bunya nut is one of the few foods which the aborigines would harvest in excess of their immediate needs. They would then take them home and bury them in moist soil, then come back in a few months and eat the 'tubers'. When the seeds sprout, they send down a rootstock well before they send anything above the soil surface. They can take up to 6 months to sprout if you plant them.

The Aborigines used to have large gatherings once every three years when there was a bumper crop. This is no doubt a strategy the trees developed to get around the swarms of sulphur crested cockatoos that rip the cones apart while they are still on the tree to get at the nuts. The bunya nut is one of the few foods which the aborigines would harvest in excess of their immediate needs. They would then take them home and bury them in moist soil, then come back in a few months and eat the 'tubers'. When the seeds sprout, they send down a rootstock well before they send anything above the soil surface. They can take up to 6 months to sprout if you plant them.

The trees apparently make good indoor potted plants because of the attractive foliage. They do not drop many leaves.

Do not loiter under the trees when they are in season. The cones are heavy and would do serious damage if they hit you, possibly killing you. Any branches that fall usually fall at this time. Rats and possums like to eat the nuts, so remember to look down as well because there will probably be the odd snake around.

Do not loiter under the trees when they are in season. The cones are heavy and would do serious damage if they hit you, possibly killing you. Any branches that fall usually fall at this time. Rats and possums like to eat the nuts, so remember to look down as well because there will probably be the odd snake around.

Note that they are not actually a type of pine. They just look like it. The grow in the high country of south east QLD and northern NSW, as well as tropical areas of QLD. They are a hardy tree and need no maintenance once established. They will grow in much colder climates, though I'm not sure whether they would produce nuts.

Most of the bunya nuts that fall in Brisbane end up rotting because people don't collect them. This creates a vermin problem and is a waste, so I have put together a list of locations where you can collect bunya nuts. I hope to extend this to other fruit that grows on public land and isn't harvested, such as surinam cherries.

Most of the bunya nuts that fall in Brisbane end up rotting because people don't collect them. This creates a vermin problem and is a waste, so I have put together a list of locations where you can collect bunya nuts. I hope to extend this to other fruit that grows on public land and isn't harvested, such as surinam cherries.

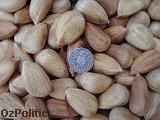

The photo on the left shows part of the 2006 harvest. OK, so maybe I went a bit overboard! If you collect a lot, make sure you de-husk them (ie remove them from the green cone) as soon as the cone falls apart easily. Otherwise it gets covered in fungus, which makes the job a bit less pleasant. Also, they may start sprouting. Neither of these issues affects the eating quality, however they do not pop on the fire unless they are fresh and they are only viable as seeds for a few months. I tried planting some last year but left it a bit late and none survived. The dehusked nuts above are the fresh 2007 batch. The cooked ones were frozen last year and then boiled, peeled and used in cooking (photo here). You can see how one of them has sprouted.

The main difficulty with bunya nuts is removing the inner cream coloured shell. I use three main methods for shelling and cooking bunya nuts.

The first involves boiling the nuts for half an hour or so on the stove, or cooking them in the microwave for a shorter period. Do not put bunya nuts in the microwave by themselves, as they will explode. The microwave method is quicker, probably uses less energy and can be used with smaller quantities of nuts. Once you have boiled the nuts, use a pair of needle nose pliers to remove the shell. It is easiest if you use a set with a thin nose, as you have to jam one of the jaws into the pointy end of the nut. Once you’ve done that, grip onto the end of the shell and pull it off the nut. You can also rotate the pliers to roll up the shell, like those old sardine cans. The nuts can then be eaten as is, or used in cooking. It doesn’t seem to harm the eating quality if you cook them twice.

Another method is to put a nut onto a block of wood and chop it in half with a machete. A meat clever or tomahawk may be a suitable substitute. You need to do a clean cut all or most of the way through the nut. Obviously, do not attempt to hold the nut while chopping it and keep your free hand well away. (Kids, ask your parents to do this bit for you.) This method is a lot easier, and cleaner too because you do the shelling outside and skip the boiling. I use a deeply serrated steak knife to get the two halves of the nut out of the shell. I usually do four nuts at a time to speed the process up, then count the eight shell halves as I find them spread over the lawn. The nuts still have to be cooked. This method may not be suitable if you are using them in a quick stir fry. If this is the case, try chopping them into smaller pieces and adding them at the start of the cooking. In fact, you should add them at the start no matter what you are cooking them with.

By far the easiest method is to cook them in a fire on a BBQ grill over a high flame. Fresh bunya nuts will split open or even explode. You may want to wear eye protection when doing this and or cover them with a pot or something. The nuts will be slightly burned in places. For eating the nuts by themselves, this gives the best flavour.

Bunya nuts can be frozen, but they may not pop open as nicely on a fire if they aren’t fresh. If you keep them to long, especially inside the cone, they will sprout. The sprouts are edible and I treat them the same way as the nuts.

Bunya nuts can be blended with honey to make a nice spread for sandwiches and toast. They are a cheap substitute for pine nuts in pesto (see recipe in basil article). They can be eaten raw when fresh, but are much better cooked. I have heard anecdotal evidence of people getting sick from raw nuts, but I don’t know how fresh they were.

One tree per location, unless otherwise stated. Notes:

* may not be productive, or the council removes the cones

# may be on private land or inaccessible

strikethrough - could not find

Please submit any corrections or new trees via email.

Brisbane southside

South Brisbane, Musgrave Park, 11 trees

West End, Ferry Rd, 3 trees, productive

Highgate Hill, Hove St

Chelmer, cnr Roseberry and Warf St, 5 tress

#Chelmer, Glenwood St

#Chelmer, Richmond St

Graceville, Simpsons Playground, near Pamphlet Bridge, 1 tree, productive, there are also some big mango trees here

Graceville, Plum Ridge st (Graceville Memorial Park), 32 trees. Either someone collects them regularly, or the council removes most of them, but you can occasionally get some here. The cockatoos sometimes strip them bare. One tree here has unusually rough bark and may be a different variety (or may be sick).

Sherwood, Strickland St, near Borden St

Sherwood, Egmont st cemetary

Sherwood, cnr Oxley Creek and Sherwood Rd

Sherwood, Galloway St

Corinda, Francis St

Corinda, Morcom Ave#

Corinda, Cliveden Ave and Lyon Ave

Oxley, Seventeen Mile Rocks Rd, near Kingsgate St

Seventeen Mile Rocks, OldField Rd at roundabout

Yeerongpilly, Stamford St

Yeeronga, William Pde, 2 trees

Salisbury, cnr Riawena and Orange Grove Road

Salisbury, Tucket Rd

Heathwood, Bentley St, 2 trees

St Gabriel's Anglican Church, Bridgenorth st, Carindale, 3 trees

#Tanah Merah, Murray's Rd, visible from Logan Mwy

Brisbane northside

*QUT Botanic Gardens, many trees

Parkland Blvd, top side of Roma St Parkland

Spring Hill, Victoria Park, 3 trees

Herston, Gilchrist Ave, Bramston Tce, also more opposite RBH?

Hamilton, Annie St

Auchenflower, Wesley Hospital, 3 trees, small cones

#Paddington, Howard St

*Paddington, Caroline St

Toowong: Glenolive Lne, Ada St, #Bellevue Pde, Herbert St

*Mt Coot-tha Botanical Gardens

Indooroopilly, along Meiers Rd and Harts Rd, starting from east end:

*Sir John Chandler Park - small

North side of road, across gully, west of radio transmitter

#Cadiz St

Thomas Park Bougainvillea Gardens, 3 trees, plus #1 in golf course

#College grounds, 7 trees

Hunter St

Underhill Ave, on Indooroopilly roundabout

#Jerrang St, at freeway overpass

#Fig Tree Pocket, Kenmore Rd, at Freeway.

Brookfield, Moggil Rd and Wybelenna St, 2 trees

#Brookfield Cemetary, Showground and Uniting Church, 12? trees

North of Brisbane

Sunshine coast, Pacific Hwy

Cooroy Railway Station

Gympie, Pacific Hwy

From Jay M:

North Arm Road 4561

Bruce Hwy, Fullager Dr, Eumundi

Bruce Hwy, Wilsons Ln, Eumundi

Bruce Hwy, Sheahans Rd, Eumundi

From Esk to Ceratodus along A3, East (E) or West (W) side of highway:

#Esk, Sth of Sandy Ck, W 2 trees

#Esk, Nth of Sandy Ck, W 3 trees in churchground

#Nth of Harvey rd near Toogoolawah, W on hill in paddock

#Moore, Main St North, E

#Moore, Forsyth Rd, W

#Moore, Sth of Himstedts Rd, W 2 trees

#Cec Krisanski Bridge over Wallaby Creek (crossing #2), Nth E 1 tree, Sth W 4 trees

#Blackbutt Range incline, W 4 trees, E 1 tree

#Nth of Benarkin turnoff, E 3 trees

#Blackbutt, Pine St, W 2 trees

#Blackbutt, Nth of Boobir Ck, W 10 trees, E 1 tree

#Yarraman Sth, E unhealthy looking

#Yarraman Nth, E 5 trees

#Sth of Berlin Rd, E 2 trees

#Nth of Berlin Rd, W 4 trees across valley

Nanango, South St, 8 trees

#Nanango, near Alfred St, W

#Nanango north, small tree, W

#Nanango, Fitzroy St, W

#Gayndah Mundubbera Rd, Nth of Black Woodmillar Rd, E

#Ceratodus, Nth of Burnett crossing, E

South of Brisbane

Mudgeeraba, Worongary Rd

Currumbin, First Ave

From Anne: Central Avenue, Eagle Heights on Tamborine Mountain. There are four trees in a row on either side of a lovely section of Running Creek.

NSW, Orange

There are two trees growing in the city of Orange NSW. One is in Cook

Park and will be 100 odd years old. Another grows behind the Fire

station and is fully grown also.

Once, in 1974, I did find a fully formed cone, just one and just once.

Orange suffers frosts to minus 5 regularly and still the trees will

produce fruit, albeit, infrequently.

I have a nice specimen in a pot now about 5 years old and very statley it is. - Len Warren

NSW, Ourimbah

you can add to the location of Bunya pine trees Palmdale Memorial Gardens, Palmdale near Ourimbah NSW ( nth west of Gosford). There are about 10 huge trees that often drop their cones and all are on a public road. I retrieved a 7kg whopper today! They love you picking them up and otherwise they have to remove them!

- Sara

Araucaria bidwillii, the bunya pine, is a large evergreen coniferous tree in the genus Araucaria, family Araucariaceae. It is native to south-east Queensland with two small disjunct populations in northern Queensland's World Heritage listed Wet Tropics, and many fine old specimens planted in New South Wales, and around the Perth, Western Australia, metropolitan area. It can grow up to 30–45 m.

The Bunya Pine is the last surviving species of the Section Bunya of the genus Araucaria. This section was diverse and widespread during the Mesozoic with some species having cone morphology similar to A. bidwillii, which appeared during the Jurassic. Fossils of Section Bunya are found in South America and Europe.

A. bidwillii has a limited distribution within Australia in part because of the drying out of Australia with loss of rainforest and poor seed dispersal. The remnant sites at the Bunya Mountains, Jimna area, and Mount Lewis in Queensland have genetic diversity. The cones are large, soft-shelled and nutritious and fall intact to the ground beneath the tree before dehiscing. The possibility that extinct large animals were dispersers for the Bunya – perhaps dinosaurs and, later, large mammals – is reasonable given the seeds' size and energy content, but difficult to confirm given the incompleteness of the fossil record for coprolites.

At the time of white settlement, A.bidwillii occurred in great abundance in southern Queensland, to the extent that a Bunya Bunya Reserve was declared in 1840 to protect its habitat. The tree once grew as large groves or sprinkled regularly as an emergent species throughout other forest types on the Upper Stanley and Brisbane Rivers, Sunshine Coast hinterland (especially the Blackall Range near Montville and Maleny), and also towards and on the Bunya Mountains. Today, the species is usually encountered as very small groves or single trees in its former range, except on and near the Bunya Mountains, where it is still fairly prolific.

A. bidwillii has unusual cryptogeal seed germination in which the seeds develop to form an underground tuber from which the aerial shoot later emerges. The actual emergence of the seed is then known to occur over several years presumably as a strategy to allow the seedlings to emerge under optimum climatic conditions or, it has been suggested, to avoid fire. This erratic germination has been one of the main problems in silviculture of the species.

The cones are 20–35 cm in diameter, and are opened by large birds, such as cockatoos, or disintegrate when mature to release the large (3—4 cm) seeds or nuts.

Although there are no reported dispersal agents for the seeds of A. bidwillii, macropods and various species of rats are known as predators of the seeds and tubers. It was observed the bush rat (Rattus fuscipes) was caching bunya seeds a limited distances uphill from parent trees, possibly allowing ridge-top germination. brushtail possums (Trichosurus spp.) were mentioned as carrying the seeds up trees. From a study in 2006, the short-eared possum (Trichosurus caninus) was shown to disperse the seed of A. bidwillii.

Natural populations of this species have been reduced in extent and abundance through exploitation for its timber, the construction of dams and historical clearing. Most populations are now protected in formal reserves and national parks.

A recent problem in small forestry plantations of A. bidwilli in Southeast Queensland is the introduction of red deer (Cervus elaphus). Red deer, unlike possums and rodents, eat bunya cones while still intact, preventing their dispersal.[1]

The bunya, bonye, bunyi or bunya-bunya in various Australian Aboriginal languages was colloquially named the Bunya Pine by Europeans. However, Araucaria bidwillii is not a pine tree (of the genus Pinus). It is also commonly referred to as the "false monkey puzzle" and does belong to the same genus as the monkey puzzle tree (Araucaria araucana).

The Bunya tree grows to a height of 30–45 metres and the cone, which contains the edible kernels, is the size of a football.[2]

The ripe cones fall to the ground. Each segment contains a kernel in a tough protective shell, which will split when boiled or put in a fire. The flavour of the kernel is similar to a chestnut.[3]

The only bunya festival recorded was by Thomas (Tom) Petrie (1831–1910), who went with the Aboriginal people of Brisbane at the age of 14 to the festival at the Bunya Range (now the Blackall Range in the hinterland area of the Sunshine Coast). His daughter, Constance Petrie, put down his stories in which he said that the trees fruited at three-year intervals.[4] The three-year interval may not be correct. The Bunya trees pollinate in South East Queensland in September, October and the cones fall seventeen to eighteen months later in late January to early March from the coast to the current Bunya Mountains. Because of heavy rainfall or drought, pollination may vary. In field research (Smith I.R.), there may be some small cones in most years, but the large festival harvests may vary between two and seven years. When the fruit was ripe, the people of the region would set aside differences and gather in the Bon-yi Mountains (Bunya Mountains) to feast on the kernels.[citation needed]

As the fruit ripened, locals, who were bound by custodial obligations and rights, sent out messengers to invite people from hundreds of kilometres to meet at specific sites. The meetings involved ceremonies, dispute settlements and fights, marriage arrangements and the trading of goods. The Aborigines’ fierce protection of the trees and recognition of the value of the timber, led to colonial authorities prohibiting settlers from cutting the trees in the 1842. The resource was too valuable, and the aboriginals were driven out of the forests along with the ability to run the festivals. The forests were felled for timber and cleared to make way for cultivation.[5]

In what was probably Australia's largest indigenous event, diverse tribes – up to thousands of people – once travelled great distances (from as far as Charleville, Dubbo, Bundaberg and Grafton) to the gatherings. They stayed for months, to celebrate and feast on the bunya nut. The bunya gatherings were an armistice accompanied by much trade exchange, and discussions and negotiations over marriage and regional issues. Due to the sacred status of the bunyas, some tribes would not camp amongst these trees. Also in some regions, the tree was never to be cut.[citation needed]

Indigenous Australians eat the nut of the bunya tree both raw and cooked (roasted, and in more recent times boiled), and also in its immature form. Traditionally, the nuts were additionally ground and made into a paste, which was eaten directly or cooked in hot coals to make bread. The nuts were also stored in the mud of running creeks, and eaten in a fermented state. This was considered a delicacy.

Apart from consuming the nuts, Indigenous Australians ate bunya shoots, and utilised the tree's bark as kindling.

Bunya nuts are still sold as a regular food item in grocery stalls and street-side stalls around rural southern Queensland. Some farmers in the Wide Bay/ Sunshine Coast regions have experimented with growing bunya trees commercially for their nuts and timber.

Since the mid 1990s, the Australian company Maton has used bunya for the soundboards of its BG808CL Performer acoustic guitars. The Cole Clark company (also Australian) uses bunya for the majority of its acoustic guitar soundboards. The timber is valued by cabinet makers and woodworkers, and has been used for that purpose for over a century.

However its most popular use is as a 'bushfood' by indigenous foods enthusiasts. A huge variety of home-invented recipes now exist for the bunya nut; from pancakes, biscuits and breads, to casseroles, to 'bunya nut pesto' or hoummus. The nut is considered nutritious, with a unique flavour similar to starchy potato and chestnut. The nutritional content of the bunya nut is: 40% water, 40% complex carbohydrates, 9% protein, 2% fat, 0.2% potassium, 0.06% magnesium.[6] It is also gluten free, making bunya nut flour a substitute for people with gluten intolerance.

A pair of bunya seedlings showing the change in leaf colour. The cotyledons are hypogeal, remaining below the ground.

Bunya nuts are slow to germinate. A set of 12 seeds sown in Melbourne took an average of about six months to germinate (with the first germinating in 3 months) and only developed roots after 1 year. The first leaves form a rosette and are dark brown. The leaves only turn green once the first stem branch occurs. Unlike the mature leaves, the young leaves are relatively soft. As the leaves age they become very hard and sharp.

In the highly variable Australian climate, the spread of actual emergence of the bunya maximises the possibility of at least successful replacement of the parent tree. A test of germination was carried out by Smith starting in 1999.[7]

Seeds were extracted from two mature cones collected from the same tree, a cultivated specimen at Petrie, just north of Brisbane (originally the homestead of Andrew Petrie, the first European to report the species). One hundred apparently full seeds were selected and planted into 30 cm by 12 cm plastic tubes commercially filled with sterile potting mix in early February 1999. These were then placed in a shaded area and watered weekly. Four tubes were lost due to being knocked over. A total of the 100 seeds placed 87 germinated. The tubes were checked monthly for emergence over 3 years. Of these seeds, 55 cones emerged from each month from April to December, 1999; 32 emereged from January- September in 2000 and 1 seed emerged in January 2001 and the last 1 appeared in February 2001.[7]

Once established bunyas are quite hardy and can be grown as far south as Hobart in Australia (42° S) and Christchurch in New Zealand (43° S)[8] and (at least) as far north as Sacramento in California (38° N)[9] and Lisbon (in the botanical garden) and even in Dublin area in Ireland (53ºN) in a microclimate protected from arctic winds and moderated by the Gulf Stream.[10] They will reach a height of 35 to 40 metres, and live for about 500 years.

|